Defining (x) Realities

Anyone who studies or talks about augmented reality and virtual reality technologies will inevitably get asked the question: but how is that augmented/mixed/virtual reality? Isn’t that more AR than VR? How one talks about these technologies is continually evolving. With every application/device that is released a version of this debate gets kicked up again, whether that’s Pokemon GO or Google Glass. These terms can mean something specific, but often get lumped in with umbrella terms like mixed reality, XR, or extended reality. Even across these terms there is significant variance between how companies/marketers/academics/enthusiasts utilize them, and differences between technical definitions and colloquial usage.

Then there is a long list of enabling technologies and other features that sometimes get associated or conflated with AR/VR, where people may ask whether something is AR or just a heads up display showing holographic content. Perhaps there is some discussion about whether an AR device/application/system employs computer vision, simultaneous localization and mapping, and gestural/haptic inputs. Without those inputs, then maybe you will hear someone dismiss it as not AR but merely a wearable device with locational tracking.

“Depending on who you ask, the definitional question is either absolutely critical or completely meaningless”

Depending on who you ask, the definitional question is either absolutely critical or completely meaningless, essential to improving public understanding of these technologies or the primary source of public confusion, philosophically interesting or mindlessly pedantic, highly impactful for technical development or largely irrelevant to actual practice.

There are no shortage of explainer charts and glossaries out there about AR/VR definitions and technologies, but these are often descriptive and fall into the same trap as others, offering an interpretation of a definition and trying to make that stick. There are also calls to move away from these loaded terms entirely, although these efforts may not resolve any definitional question but instead simply move the debate from ‘what is augmented/mixed reality’ to ‘what is the metaverse.

’This post attempts to explain the debate and demystify it for new and old scholars alike, and to explain some of the underlying motivations for why people care about the question and how to talk about it productively.

“if you find yourself wanting to ask the question ‘but is that really mixed reality’, maybe first ask yourself why it matters and why you are doing it?”

The Definitions, Taxonomy

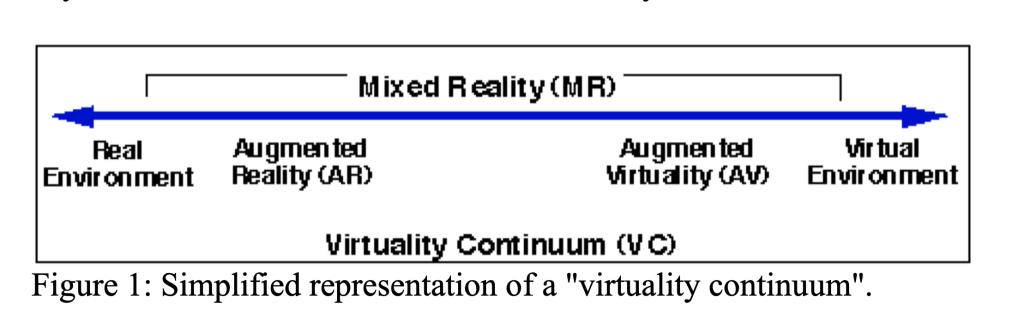

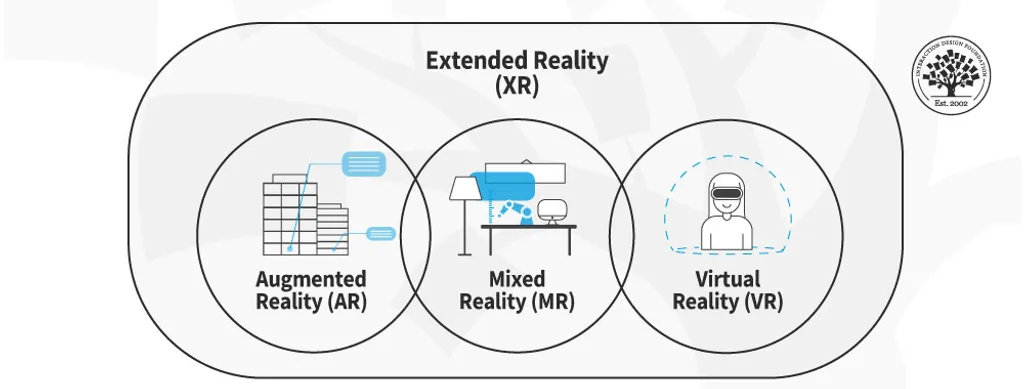

At the highest level, there is a class of visual technologies that generate spatial, interactive, and/or digital assets that extend reality (XR). Within this broad categorization these split into augmented or virtual reality technologies, differentiated by the degree to which the technology interacts with physical space. VR technologies recreate/replace physical perception of space, while AR technologies exist atop of and interact with physical space. The mixed reality spectrum, coined by Milgram and Kishino (1994), explains how AR/VR technologies are similar based on the degree of virtual interaction/replacement of physical reality, which dictates whether a technology is augmented reality, augmented virtuality, or virtual reality (Milgram & Kishino, 1994). One point of confusion with this graphic is that while VR exists on one end of the pole of the reality-virtuality continuum, it is not technically Mixed Reality (MR) because it does not merge with the real environment.

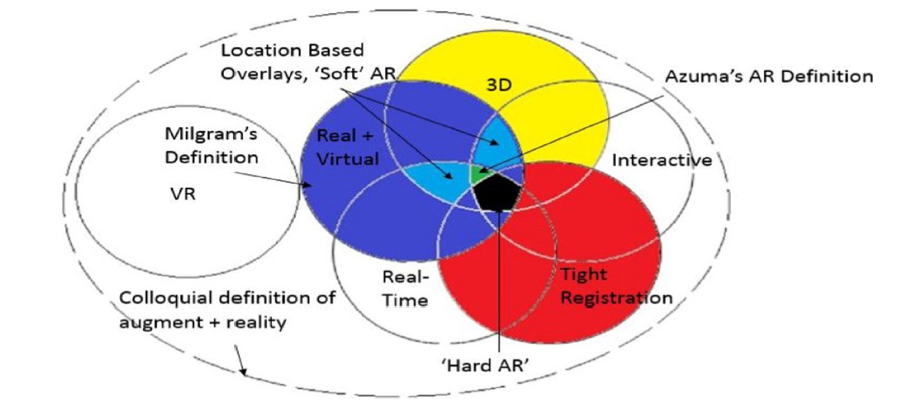

Milgram’s mixed reality spectrum was useful for distinguishing AR from VR, but it is more a definition of exclusion (does not replace reality) and only provides one criteria (integration of virtual graphics with physical space). The Azuma (1997) definition further clarified this to say that AR technologies not only had to 1) combine the real and the virtual but also 2) be registered in 3-Dimensional Space, and 3a) be real-time and 3b) interactive.

This has been the dominant academic definition of AR for decades now, but the interpretations and applications of these criteria have been subject to debate. Take, for example, the famous 1st and Ten line that was first introduced to American Football broadcasts in the late 1990’s, which shows several imaginary lines on the field that players move over. One might argue that it is registering the colors of the fields and players in 3-Dimensional space, while others say that it simply visualizes the line on a 2-D broadcast. Real-time is already a question of degrees, but some would argue that the line is real-time in that it updates and changes without perceptible delay, while others argue that there is still some delay built in where the line gets superimposed on the broadcast to make this system functional. Lastly, the question of interactivity is open to interpretation, in that the system very much interacts with objects in the field of play, but is not something that users can interact with in any way. Based on one’s interpretation of Azuma’s criteria, then, these graphics on sporting events are either the most successful and mainstream AR applications in the world, or simply a time delayed color sensor/recognition system that displays that animates a televised broadcast (not AR).

This of course is just one system, but every application could run into some ambiguity regarding an interpretation of Azuma’s criteria. With some of the earliest ‘AR’ browsers like Layar and Wikitude, because they overlay visual geolocational data onto a phone, does that meet the ‘real-time’ if the data is fairly static and could be weeks or years old, and does that meet the interactive criteria since the assets are just floating in locational space, not necessarily interactive with the events occurring in that space. With the Azuma definition there are different camps in terms of how to apply the criteria, as well as disagreement as to whether technologies needs to meet all of the criteria to be called AR by the strict interpretation of it, or if mostly there is close enough (e.g. Mobile AR Browsers, Google Glass, Pokemon Go, etc.).

Some scholars and practitioners of AR have implicitly added criteria to the original Azuma definition, whether by technological proxy or just to distinguish themselves from public applications. Some even called this ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ augmented reality, with hard AR being characterized by multiple real-time holographic/camera tracking and registration systems, location mapping and computer vision algorithms, and hand/gestural tracking and interactivity with augmented objects. Here is an example where things one level below the stated criteria (e.g. the devices and technologies used to bring about these experiences), get added as necessary components to being ‘AR’ or ‘VR’ or used to distinguish between a particular type of AR (hard) versus geolocational AR browsers (soft). A graphical representation of this definitional debate is seen here, from one of my research articles about this precise issue and competing interpretations/criteria.

The Politics of Definitions: Who Gets to Say?

Many in the field who have confronted or had to answer these questions many times have opined, is this a productive conversation and why does this matter? Should we continue to enforce the boundaries as defined, however messy, uncomfortable, and unpopular that may be for the technology? Or should we move away from these terms altogether, coalescing around something else or hope that some company comes along to become the de facto lexicon, just as people now say they are ‘Googling’ something as opposed to ‘using a search engine query for information’?

Academics have long understood that definitions matter in ways that go beyond the specifics, more that definitional questions are ones of boundary drawing, consolidating power, and exerting power using that definition (Bowker & Star, 1999). Understanding the definitional question through this lens helps make sense of this conversation beyond the question of interchangeable terminology and specific criteria.

First, AR was gaining traction as a defined area of study just as VR technologies in the 1990’s had been overhyped and been a commercial failure. For a variety of reasons, materially and discursively distancing the technology from VR became an important motivation for the AR move and the AR criteria, hence the importance of protecting that boundary. Some of the first workshops and conferences in this area, the International Workshop on Augmented Reality, later the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), explicitly adopted the Azuma criteria and made it clear that they were distinct from VR and that VR papers should be presented at other more generalized conferences.

The rise of corporate actors into the AR space often drew the ire of these communities, because they used the term augmented reality/mixed reality more as a marketing and promotion tool rather than a technical term. Posts pointing out how Google/Microsoft/Magic Leap were misusing the terms were part of that boundary work, as were the various primerson these terms to explain/standardize the definition.

The hard/soft distinctions and additional criteria can also be understood as a response to these outside corporate actors trying to reclaim the term, where academics worried that these applications seemed too mundane, unsophisticated, and unappealing to be associated with their work. While having companies demonstrate successful applications may be beneficial people’s general understanding of their academic areas, it could also diminish their importance as authorities and suggest that the technical problems they are working on are already solved (e.g. AR/VR has arrived). Seen through this lens, then, for many the motivation behind enforcing the strict academic definition is to prevent unpopular/negative associations, show that the problems within the field are still unsolved, and preserve their authority as definitional gatekeepers. The places where academics have authority over these definitions tend to be amongst themselves and through peer review in journals and conferences, but this is enforceable only as long as that power is respected and entities care about their acceptance. If Microsoft wants to call all of their AR and VR products Mixed Reality™ and try to rebrand it in a way that is not how Milgram and Kishino defined it, there is not so much people can do about it except to write another critique about how the terminology is confusing.

Has Reality been defined for you?

Consider who is asking, why they care, and whether it is important to you.

While definitions are political by nature, not everyone is explicitly being political when they enforce a definition. First, there are many academics who honestly believe that it is necessary to prevent confusion, as they feel the terms would be meaningless without any criteria so you have to draw the line somewhere, otherwise technologies like a Kaleidoscope or Photoshop could ‘augment’ one’s perception. Amongst the academic community, at least internally we need to be able to distinguish between markerless AR and marker-based AR, computer vision algorithms versus geolocational data, etc., so it’s not a stretch to then argue whether technologies that employ one or the other meets the criteria of interactivity, real-time, etc. If it is important to people to say present at conferences where these definitions matter and are enforced, then engaging in these debates is important at least to bypass the gatekeeping that enforces these definitions. The degree to which one feels the need to try to extend this definitional battles to private companies trying to utilize these terms and public understanding of AR/VR/MR etc. is up to the individual and if they feel that public understanding needs to line up with agreed upon academic convention.

Then there are individuals who try to enforce certain definitions not just for the sake of clarity and having a clear dividing line, but for the purported ‘good of the technology. This is typically a group of self appointed AR/VR promoters/evangelists who are invested in the technology and are working to ensure that it is successful. Some of these people may have overlearned the lessons of the VR experience in the 1990’s or simply want to push toward a positive/impactful world of AR/VR, and use the definitional debate as a proxy to weed out applications they see as mundane or harmful. While there is nothing inherently wrong with being a promoter and wanting the technology to have positive public associations, it is important to note that these are self-appointed arbiters of what is good and bad, which is already subjective, and more so when they are inconsistent in their application/enforcement of criteria. For example, some might want to bend the interactivity criteria to include 1st and Ten and Pokemon GO because they are popular but then wield the same criteria to exclude Google Glass and Magic Leap because they were commercial failures, which can feel arbitrary, opportunistic, and confusing in it’s own right.

It probably will not stop people from trying to do the definitional dance, but trying to clarify higher order criteria as a proxy for limiting out specific technologies or uses does not make much sense. If one really does believe that AR is defined by a set of criteria, then it simply is a technology that allows for a range of things such as visually displaying 2D/3D content, interacting with that content, and enhancing/diminishing one’s reality. That says nothing about content and what someone does with it, so AR/VR is dual use in the same way the internet is, and people can use AR/VR for all of the same amazing and destructive ways. If this is the motivation for someone to ask about definitions/boundaries, my thought is that the better way to deal with this is simply to call something a bad AR/VR device/application, rather than try to perform definitional gymnastics to define it outside of the technology.

Lastly, there is an element of the definitional debate that serves as a social signifier, a marker that one is part of the in crowd that understands these differences and can call out those who do not. As a practical matter, then, one has to decide whether they want to adopt and use the terminology in the intended way to also reinforce this identity and to increase mutual understanding, or to disregard these conventions and deal with the occasionally obnoxious and self-important correctives and questions about whether you understand that this technology is X, Y, Z.

If one chooses to adopt the Milgram and Kishino Mixed Reality spectrum, the Azuma criteria for AR, and the umbrella terms of XR or Extended Reality, there is nothing wrong with that as long as you understand those terms, the limitations/disputes about those terms/criteria, and you can discuss your work within and around that system. If one chooses not to use these definitions and instead adopt alternative terms, then as long as they can tolerate and push past the questions of why and can explain exactly what they mean in terms of the technology in productive ways, then that is also an acceptable choice. Lastly, if you find yourself wanting to ask the question ‘but is that really mixed reality’ at a panel or conference, maybe first ask yourself why it matters and why you are doing it, and whether there is a more interesting question you have about their specific application of the technology.

References

Azuma, R. T. (1997). A survey of augmented reality. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 6(4), 355-385.

Bowker, G., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out. Classification and its consequences, MIT Press.

Liao, T. (2016). Is it ‘augmented reality’? Contesting boundary work over the definitions and organizing visions for an emerging technology across field-configuring events. Information and Organization, 26(3), 45-62.

Milgram, P., Takemura, H., Utsumi, A., & Kishino, F. (1994). Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. Telemanipulator and telepresence technologies.

Liao, C. (January, 2022) Definitional Realities. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). link

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.