Notes on Helsinki’s Digital Fashion Week

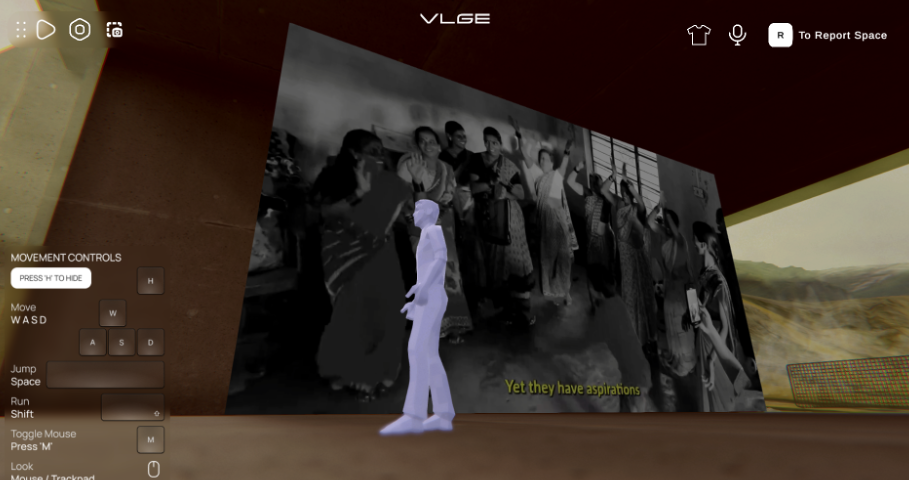

In late August of 2024, Helsinki Fashion Week (HFW) was held on online, world-building platform VLGE. Still accessible via their Instagram Link Tree, I’ve explored up to 40 different digital fashion exhibitions. When done right, digital technologies can enable users to build alternative and immersive fashion experiences. The following is a review of the digital HFW event in response to selective fashion and trend theories. You can read my initial review of the event here at Ensemble Magazine.

The following review relies on a specific definition of fashion: that fashion is a trend-based phenomenon not limited to the apparel industry. According to Simmel (1957), fashion is an outcome of a dialectical relationship between the individual and collective. Simply put, individuals align themselves with particular social groups and positions through dress while simultaneously striving to identify themselves as individuals. Carter (2003), writing on Simmel, explains that “if the desire for uniformity and imitation could reach fulfilment there would be no such thing as fashion, only mass similarity” (p. 67). The same would be true if everyone had unique and eccentric tastes; there would be no trends to follow and therefore, no more fashion.

Furthermore, Walter Benjamin (2002) explains that fashion does not represent a progressive, linear model of history and time but rather a non-linear, cyclical model. Referencing previous styles, and reconceptualising and presenting them as ‘new,’ is crucial to the fashion process. Through the Tigersprung, the leaping between different historical planes, fashion can reference itself and seize a previous moment expressed by the collective as being important for the present (Lehmann, 1957). For Benjamin, this collective power is specific to the oppressed and working classes. The dialectical image that flashes in the present unconsciously announces a wish image of a previous collective to those of the contemporary moment. This process is what Benjamin argues disrupts the dream state or phantasmagoria of the present working classes, to inspire them to revolutionary action. Therefore, fashion’s revolutionary potential is in its ability to interrupt and reveal alternative histories to those written and disseminated by the elite, disrupting the continuous and linear flow of history and progress (Buck-Morss, 1989).

The meeting of fashion and the digital

What does this mean for digital fashion events? The use of digital platforms for fashion exhibitions and events are still in their infancy, although HFW was a frontrunner in this space. Firstly, while digital fashion visualisations are relatively novel, they ultimately lack a familiarity for an everyday fashion consumer, meaning trends are unlikely to be distributed. Secondly, when familiarities, and ultimately, historical references are lost, potential political reminders, as according to Benjamin, are also lost.

A tension between using a digital platform that is lumped together with ideas of innovation and industry transformation, while also trying to create worlds that are still recognisable for fashion consumers, is an interesting problem these events will continue to grapple with.

For example, the SHILOKAVICA exhibit centres around enlarged avatars of demonic variants. This space moves beyond fashion marketing; rather, it is representative of a creative spirit—something that is expressive and rebellious. While the silhouettes of the garments might not represent material fashions, the avatars tattoos are recognisable, as tattoos and body adornment are not immune to trend cycles. Tattoo styles featured on these avatars are reminiscent of stick and poke figures and tribal-like cyber sigilism. There seems to be an obvious tension between the recognisability of the tattoos and the distinctiveness of the character design. While a consumer might not aspire to recreate the devil’s look, they might see parts of themselves in the tattoos represented.

In terms of expressing alternative fashion histories, the OffGrain exhibition stands out as particularly effective. The exhibit serves as a tribute to the Kuruba people and their distinctive textile and pastoral practices in Kandoli, a village in Karnataka, India. The exhibition space, along with the garments and accompanying media, is dedicated to highlighting the Kuruba’s woollen textile traditions, which are increasingly endangered by economic pressures and environmental challenges. While it might not be a subconscious reminder of a collective past, through a repetition of fashion silhouettes, the exhibit’s use of diverse, interactive media facilitates a cohesive narrative, fostering an immersive experience that resonates effectively with online audiences.

Innovation and sustainability are at the forefront of HFW’s mission. What is often highlighted as creative potential for these platforms is to expand past what is possible in the material world. For example, Zero Waste Every Waist, while presenting pretty standard fashion imagery, stages their world as a trash palace that is a dystopian prediction into our future. Shiu_studio displays silicone textured sculptural objects and clothing on uncanny valley avatars defying laws of gravity. ISADOSKA’s collection titled Tropisms, inspired by the adaptability and transformation of mother nature, has a scaled up an iridescent naked woman emerging from a pond, with flowers growing from her mouth.

There are also many limitations to the VLGE platform. Firstly, you must build your fashion exhibition in selected spaces provided by the platform itself. There are multiple spaces, including gallery-like white cubes or enclosed rooms made of metal, stone or wooden finishes. Others are open landscapes: of rolling hills, with clouded or pink skies and bodies of water that you can awkwardly swim in. The spaces themselves also have limitations—with invisible barriers marking their territory and rendering your avatar immobile. Furthermore, the garments presented are not purchasable or compatible with any other digital environments. This is a reminder that digital spaces also have material constraints, both hardware, software, and user experience orientated.

“To pursue a digital-only fashion event is to weigh the lower costs of production and potential democratising power against the environmental impact and effectiveness of the event and experience itself.”

Digital also doesn’t necessarily mean more sustainable either. Conveniently aligned with pandemic restrictions limiting physical events, HFW launched its first digital fashion week in 2020, intending to offer a more sustainable experience through immersive digital spaces. Partnering with carbon accounting firm Normative, HFW succeeded in significantly reducing the event’s carbon footprint per visitor from 137kg to 0.66kg CO2e. However, it is essential to note that while this reduction per visitor was notable, the overall carbon footprint of the event was estimated to be higher. Although there are no official reports available for HFW 2024, it is important for digital fashion reporting to be aware of the very material outcomes of the information and communications technology sector.

To pursue a digital-only fashion event is to weigh the lower costs of production and potential democratising power against the environmental impact and effectiveness of the event and experience itself. While I’m not convinced that an entirely digital fashion week is set to replace physical events any time soon, there is potential for digital spaces to complement physical experiences, elevate marginalised voices, and project them further than what was possible of a local (mediated) runway event. Ultimately, the revolutionary potential these spaces have to offer are all the captivating qualities present in the concept of fashion already. Fashion connects the individual and collective, that highlights promising moments from our past. As expressed by Benjamin (2002), it is a fetishised capitalist commodity with political and revolutionary potential. Ultimately, digital fashion events could serve as a medium to make visible the cyclical connections within style, turning fashion into a collective act of remembering that resonates across time.

References

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. 1st paperback ed, Harvard University Press, 2002.

Buck-Morss, Susan. The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. MIT Press, 1989.

Carter, Michael. “Georg Simmel: Clothes and Fashion.” Fashion Classics from Carlyle to Barthes, 2003.

Chan, Emily. “Are Digital Fashion Weeks Really More Sustainable?” British Vogue, 17 July 2020, https://vogue-int-rocket.prod.cni.digital/whats-carbon-footprint-of-digital-fashion-week.

Lehmann, Ulrich. Tigersprung: Fashion in Modernity. MIT Press, 2000.

Simmel, Georg. “Fashion.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 62, no. 6, 1957, pp. 541–58.

Zhang, Tianwei. “Digital Helsinki Fashion Week Saw Significant Drop in Carbon Emissions.” WWD, 30 Sept. 2020, https://wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-features/digital-helsinki-fashion-week-saw-significant-drop-in-carbon-emissions-1234613901/.

Recommended citation

Stevenson, T. (November, 2024). Notes on Helsinki’s Digital Fashion Week. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). https://cavrn.org/notes-on-helsinkis-digital-fashion-week/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.