Interviews

Case Study One: The politics of space in Pokémon Go

Duis nunc eros, mattis at dui ac, convallis semper risus. In adipiscing ultrices tellus, in suscipit massa vehicula eu.

By Someone Somethingsson

August 30

Its July 2016, 21 years since the original release of Pokémon Red and Green for the Gameboy, in which players travel the virtual environment to catch virtual creatures called Pokémon. Unlike the Gameboy game, where this encounter with Pokémon takes place in the virtual space resembling the Japanese region of Kantō, players of Pokémon Go wander the streets of the real-world city to ‘catch ‘em all’. The game uses smartphone-based AR rather than playing the game on the screen of a Game Boy. Players are notified on their phones when they have encountered wild Pokémon. They pick up their phones and move the device around them – using the phone’s camera to scan the environment. Eventually, a digital rendition of a Pokémon appears, overlaying the image of the physical environment captured by the camera. Pokémon in this way came to inhabit a wide range of spaces from schools, to supermarkets, to funerals and memorials.

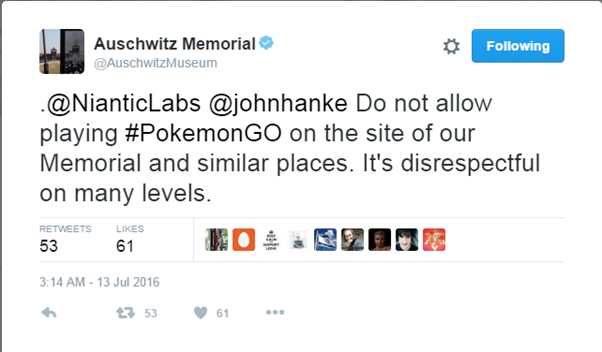

The result was conflict; between physical property laws and the developer Niantic’s ability to repurpose existing public and private spaces for augmented play. People found their homes transformed into virtual playgrounds, and many others complained to the police in response to the rapid and unexplained increase in foot traffic in parks and other public spaces (YeeFen Lim, 2020). Private businesses quickly sought the ability to remove, or host, Gyms or Pokéstops to capture this attention, and in 2019, Niantic settled a lawsuit brought by US homeowners that in response to this issue – what rights do technology companies have to dictate digital layers over existing physical spaces that already have established legal, cultural and social norms?

Other issues around the politics of space in Pokémon Go also emerged. Writing in Overland, Brendan Keogh (2016) makes the comparison between the experience of playing Pokémon Go and the 19th century figure of the flaneur, a figure from the work of Baudelaire – a typically socioeconomically privileged, white man who experiences urban space not out of the usual, purposeful motivations for movement, but through a kind of urban drifting or wandering. The comparison between the flaneur and the Pokémon Go player is, at the face of it, an easy one. Many found themselves wandering the streets with the hope of stumbling upon a rare and powerful Pokémon, moving around the city in ways that differed from usual motives.

“People found their homes transformed into virtual playgrounds, and many others complained to the police in response to the rapid and unexplained increase in foot traffic in parks and other public spaces.”

But, Keogh notes that both the flaneur and the Pokémon Go player and their engagements with the city, are not free of politics. The politics of class, gender and race characterise these practices of moving throughout the city, much as they characterise playing Pokémon Go. As he puts it, “A nineteenth century woman would have a hard time being a flaneur”, much would a non-white person in city spaces, people who are disproportionately targeted and profiled as potential threats by police.

As Keogh puts it, “the non-white person who dares stroll around the city without clear purpose is seen as suspicious, as a loiterer, and might attract the attention of law enforcement – attention that continues to be a potentially deadly affair for black men in Western countries”.

The broader politics of these spaces – grounded in geospatial technologies which have histories of capture and control for the US military – often also go overlooked. Niantic has its roots as CIA-backed geomapping software company Keyhole Inc (led by current Niantic CEO John Hanke). Keyhole was responsible for developing defence mapping software for use in the Iraq war. In 2004, Keyhole was acquired by Google and instrumental in the development of Google’s mapping software, Google Maps – a now heavily monetised wayfinding application.