Avoiding the (Virtual) Hype

Inevitably, a big 2023 story will be Apple’s release of their long-rumored XR headset. For years, news and tech websites have published minutiae of the project, quoting supply chain analysts’ claims it will be “the most complicated product Apple has ever designed” as well as “a game-changer for the headset industry.” While fans may be planning to queue up at Apple stores to get their hands on these high-priced HMDs, for industry-followers (e.g., academics, media makers) such stories seem all too common and devoid of key issues like privacy, accessibility, or even practical use-cases of the technology. That is the focus of this post; I suggest that a promotional media ecosystem has long propped up narrow views of VR, its potential and problems. I will then offer some advice garnered from game and tech journalists about how to frame and consume stories about virtual reality.

Virtual Reality’s Media Ecosystem

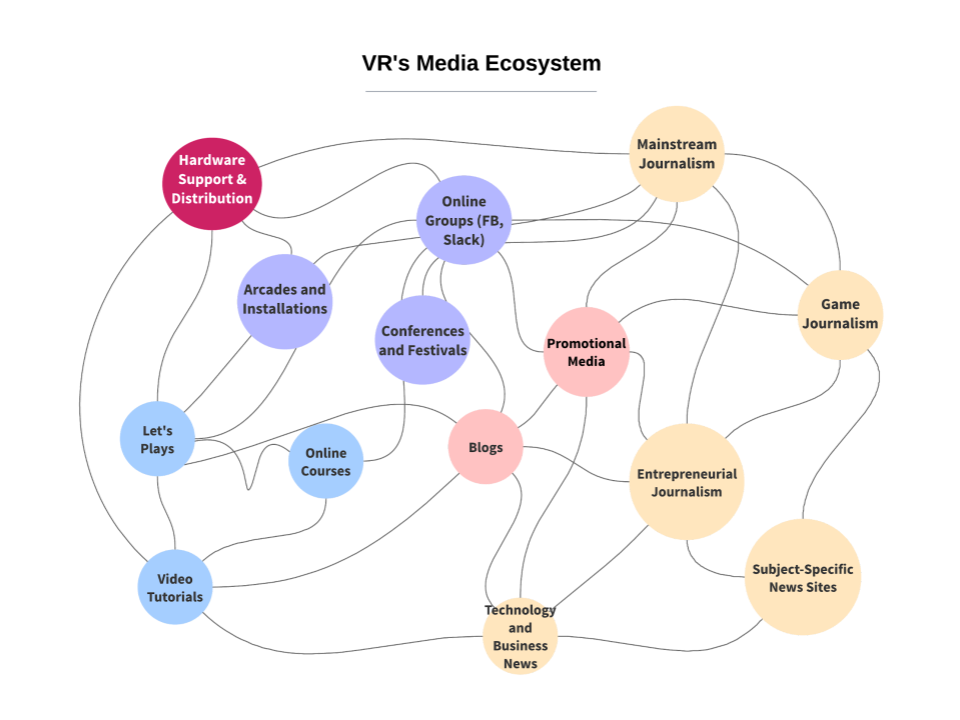

When commercial headsets like the Oculus (now Meta) Rift and HTC Vive were released, I mapped out a media ecosystem (Foxman, 2018). I was performing participant observation of VR’s early adopters in New York City, attending meetups crammed with many people who still post about Apple and other XR products. Those messages were one node in a complex media network for circulating VR information.

This interwoven network of bloggers, newsmakers, influencers, online forums, and physical festivals still exists even if platforms like Facebook groups have shifted to competitors like Discord. Mainstream, games, tech, and subject-specific (e.g., Upload VR, VR Focus) journalists shared information and, more importantly, space with amateur developers, entrepreneurs, and influencers. They were learning from and referencing each other’s work at a moment when newsmakers were heavily investing in the technology. Paradoxically, these writers needed to objectively evaluate commercial VR’s viability while simultaneously relying on enthusiasts and early adopters to better understand its use and endorse their journalistic content within the ecosystem.

The circulatory nature of this information sharing was promotional and ambitious, typically espousing VR’s social and economic aspects (p. 109), while hedging that its main use was for gaming (p. 111). VR was framed as an innovation whose benefits could touch almost any profession (including journalism itself). Its revolutionary potential was on the horizon and required a collective push from those within the media ecosystem to realize. This narrow perspective has consequences: perpetual portraits of VR’s state of “newness” (Harley, 2022); assumptions about the appropriate companies to herald the technology (Egliston & Carter, 2020); deep association with gaming culture (and some of its more toxic elements) (Evans, 2018; Golding, 2019); and connection to obscure and culturally problematic (if optimistic) concepts like empathy (Nakamura, 2020). In fact, I found that journalists writing about VR and empathy similarly defined the latter term aspirationally without a clear understanding of its scientific underpinnings (Foxman et al., 2021).

“Hype and anticipation about VR still grace the pages of many websites even while, for some, everyday use is commonplace”

In other words, the media ecosystem surrounding VR seems to foster murky coverage rife with hopeful yet unclear expectations (and letdowns) of the technology’s promise, while disregarding critical concerns about power, control, data, politics, and demography in its application. Hype and anticipation about VR still grace the pages of many websites even while, for some, everyday use is commonplace.

Advice for Future Coverage

So, what can those (whether academics or journalists) writing about VR do to combat the norms of this promotional media ecosystem? Moving beyond the excitement and lack of clarity regarding VR’s future seems like a good start, but for other practical solutions, I want to turn to my recent report on how coverage of virtual worlds (including those facilitated by VR) changed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Foxman, 2022). During the pandemic, VR was framed (again) as a future technology that could help us congregate synchronously, but not quite effective enough compared to apps like Zoom or video games like Animal Crossing. However, when I questioned journalists about this coverage, a few salient pieces of advice emerged:

First, discontinuing reportage of one specific headset, title or experience can break the anticipatory cycle of hardware releases that dogs XR coverage.

Second, avoiding the hype around new terminologies and technologies was encouraged. While interviews occurred before Meta’s rebranding, reporters were skeptical about the metaverse and recognized it was already “here. It’s just fragmented. So maybe it’s not quite as meta as we aspire for it to be for better or worse.” Generally, writers reminded me that news outlets should refrain from the prognostication found in VR’s media ecosystem and instead focus on tried and true on-the-ground reporting.

Third, and related, they advocated concentrating on people over platforms as there are already diverse and interesting communities (not to mention sources) embedded with virtual environments. Spending time within them in a social space like VRChat would net meaningful stories from people who consider the medium integral to their lives.

These three key points reflect some of the report’s findings, which also take into account massive multiplayer online games, livestreaming, and other forms of virtual meeting spaces. However, at its root, the reporters’ counsel serves as useful guard rails for writers and readers of VR coverage: to move beyond hype cycles and think more about the present as well as those in power and empowered by this not-so-novel technology.

References

Egliston, B., & Carter, M. (2020). Oculus imaginaries: The promises and perils of Facebook’s virtual reality. New Media & Society, 1461444820960411.

Evans, L. (2018). The Re-Emergence of Virtual Reality. Routledge.

Foxman, M. (2022). Lessons for Journalists from Virtual Worlds. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/lessons-for-journalists-from-virtual-worlds.php

Foxman, M. (2018). Playing with virtual reality: Early adopters of commercial immersive technology. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8M05NH3

Foxman, M., Markowitz, D. M., & Davis, D. Z. (2021). Defining empathy: Interconnected discourses of virtual reality’s prosocial impact. New Media & Society, 23(8), 2167–2188.

Golding, D. (2019). Far from paradise: The body, the apparatus and the image of contemporary virtual reality. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25(2), 340–353.

Harley, D. (2022). “This would be sweet in VR”: On the discursive newness of virtual reality. New Media & Society, 14614448221084655.

Nakamura, L. (2020). Feeling good about feeling bad: virtuous virtual reality and the automation of racial empathy. Journal of Visual Culture, 19(1), 47–64.

Recommended citation

Foxman, Maxwell. (Jan, 2023) Avoiding the (Virtual) Hype: How Journalists Can Deal with VR’s Promotional Media Ecosystem. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). https://cavrn.org/avoiding-the-virtual-hype

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.