Facing the socialisation of augmented reality

Fifteen years ago, a grad student named danah doyd was finishing off her dissertation titled Taken Out of Context: American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics exploring how teens were leveraging newly forming social media to live their lives in novel ways; boyd spotted people and publics coming of age in new ways.

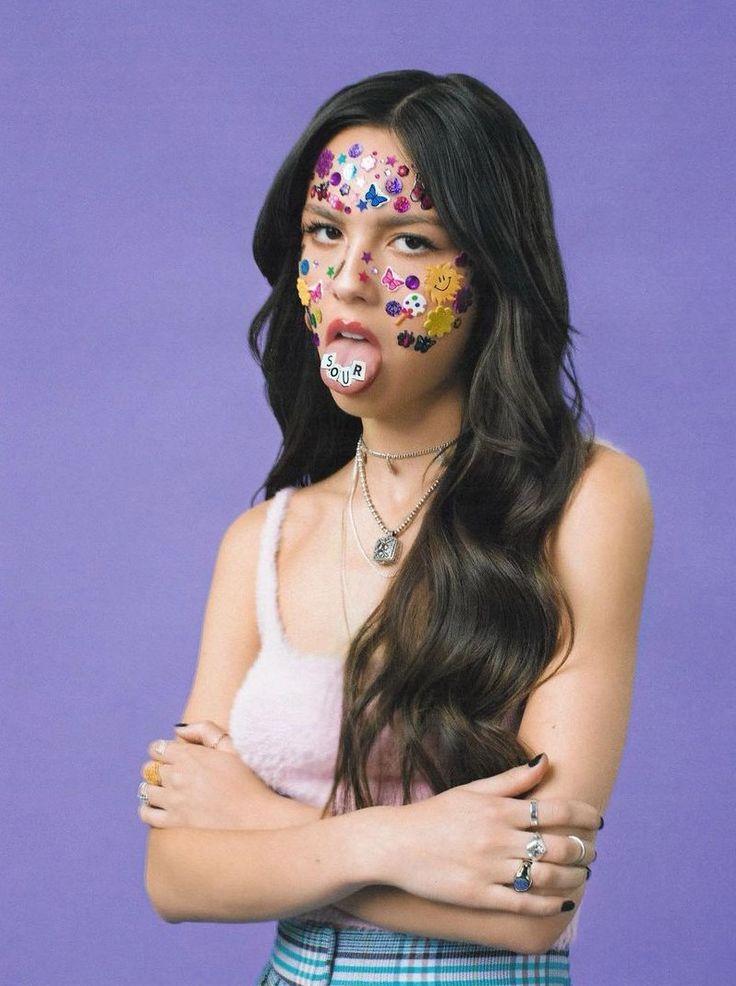

It’s useful to return to boyd’s early work to start thinking about how novel augmented publics are starting to socialise, including how the properties and dynamics of AR might afford new types of publics. And I’m going to use former Disney channel star Oliva Rodrigo – or more specifically her presentation of face – to do so.

boyd’s work argued that social media changed how teens were configuring identity, socialising (with) peers, and interfacing with adult society. Social media were new spaces, where invisible audiences, context collapse, and the blurring of public and private were gathering steam.

Her deeply ethnographic work also pinpointed how the properties and dynamics of the networked media afforded such shifts. Persistence, searchability, replicability, and scalability all afforded these networked publics. For instance, the public articulation of Friends online (as opposed to having friends) required evolution of both the concept of friendship and how to manage it.

I note here that AR media do and will have their own properties and dynamics. Some of this has to do with new ways of thinking about surveillance. Kent Bye (2021) counts 64 different physiological and biometric data streams that are being captured for AR and VR technology designs, while SLAM instantaneously creates an intimate map of your surroundings that can interface with data from the cloud.

Elsewhere I’ve used the term biospatial surveillance to signal how AR requires incredible amounts of biometric capture and analytics, while also intimately mapping users’ immediate environment. For AR to be social, these data won’t stay on device.

“I’ve used the term biospatial surveillance to signal how AR requires incredible amounts of biometric capture and analytics, while also intimately mapping users’ immediate environment.”

Which brings us back to boyd, who knew that what networked publics looked like and felt like would continue to evolve. As boyd put it at the time “publics will continue to be transformed [in] the interplay of new technologies and their adoption.” (2008; 301). Indeed, she concluded her thesis with a recognition that newly released smart phones were creating social and technical contexts for “mobile networked publics”. In those final pages she experimented with the neologism (dis)locability to describe the network interactions that are “simultaneously independent of and deeply connected to physical location” to consider “how physicality and spatiality will intersect with networked publics.” In 2008 this was seeing for the first time the pale blue dot of you on Google’s map of the world. In 2022 features like Snapchat’s Snap Map congeal blobs of these locatable networked public interactions, geographically signaling cultural happenings.

Faced with spatial contexts: Considering sociality in augmented publics

AR/VR exponentially increases networked ‘(dis)locability’ not in geographic terms but corporeal ones, spatialising body and environment. Biospatial surveillance intimately measures the physical location not only of the immediate surroundings, but of features and gestures of faces. Such mapping makes us reconsider how AR might socialize us, and how we might socialize AR. And here AR’s adoption has less to do with the newest enterprise focussed AR/VR solutions from major tech first than you’d think.

Which (finally!) brings us to Oliva Rodrigo’s face. While the implementation of biospatial surveillance and their consequences might seem far off, consider that over 250 million of Snapchat’s 340 million users use AR functionality daily. A whole generation of social media users are coming of age with their datafied face as a new type of interface to their peers.

Major media are catching on to what the teens are up to. Olvia Rodrigo’s break out album and first single Brutal was explicit in how teens just like her could augment their identities through AR tools provided by her technology partner Apple.

The socialisation of bio-physical surveillance is already here, but as these things go, just not evenly distributed yet – with the fun filters and lenses giving a generation a gateway into what augmented publics will come.

How this socialisation of AR technologies progresses, is not only written on Meta’s metaverse wall – teens like Rodrigo and her fans are rewriting what can be written, where, by who, once again. And while I can’t speak for boyd, I do get déjà vu, watching people and publics coming of age in new ways

References

boyd d (2008) Taken out of context: American teen sociality in networked publics. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California, Berkeley.

Recommended citation

Heemsbergen, L. (December, 2022) Facing the socialisation of augmented reality. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). https://cavrn.org/facing-the-socialisation-of-augmented-reality/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.