Picturing Early Virtual Reality

Recently, we submitted our VR book – Fantasies of Virtual Reality – to the publisher, at which point we turned our mind to the much-neglected art log. This has been, for Marcus in particular in the past week, quite the rabbit hole, where we learnt more about the earliest history of VR and further developed our deep respect for archivists.

The Sword of Damocles

The early origins of (digital) Virtual Reality are frequently recited in histories of VR and AR.

Most of the attention focuses on Ivan Sutherland who had developed Sketchpad in as part of his PhD thesis published at MIT in 1963 (an achievement for which Sutherland won a Turing Prize in 1988). Sutherland is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of computer graphics.

Following the completion of his doctorate, Sutherland took a job at the National Security Agency, before taking on a position in the US Army as a first lieutenant, in which he headed the US Department of Defense Advanced Research Project Agency’s (DARPA) Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) from 1964-1965.

It was after his tenure as DARPA head that Sutherland, now working at Harvard, along with his doctoral students Bob Sproull, Quintin Foster, and Danny Cohen developed the ‘Ultimate Display’ – a computer display with a head position sensor, which meant that the display could change based on movements of the head – what is often described as the progenitor to VR.

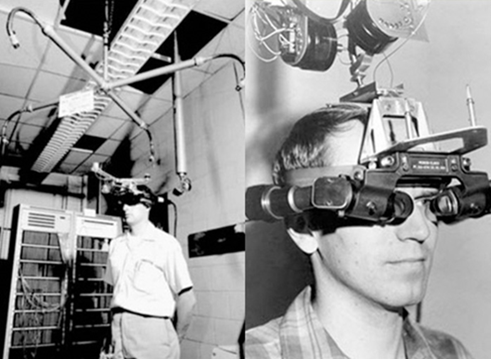

First demonstrated in 1968, the system was nicknamed ‘Sword of Damocles‘ because of the intimidating mechanical structure suspended above the user, necessary for tracking changes in the position of the screen so that the image could be updated. The experience of Sutherland’s display was more similar to Augmented Reality, because the display was actually see-through, similar to something like the Google Glass.

Figures 1 & 2: Ivan Sutherland’s Sword of Damocles VR headset.

Now, in most histories of Virtual Reality one of a few available black and white images of the Sword of Damocles are used. These are either from Sutherland’s 1968 paper, “A Head-Mounted Three Dimensional Display” (Left) or from his Turing Award website (right). Great photographs, but neither are in the public domain and available for use in a commercial book.

In 1968, Sutherland moved to the University of Utah where he worked with David C Evans, pioneering early computer graphics research and establishing one of the most influential early computer science programs. They founded Evans & Sutherland, a computer graphics firm still in operation today, and continued doing military contracting.

In Search of Image Permissions

In our search of a photograph of Sutherland’s early VR system that we could secure permissions to use, Marcus contacted the University of Utah’s archives, hoping that something might be found in the David C. Evans photograph collection. We quickly heard back from their Photo Archivist, who informed us:

“You are not the first person to ask and I have looked for it many times! It is not in the David Evans photograph collection or the University of Utah Computer Science photos, and we do not have a Ivan Sutherland collection.”

They did provide us some helpful tips on how to navigate the university’s archives, and so armed Marcus went through every key-word he could think of for finding more documents about Sutherland’s early VR system, which, of course, was not commonly called VR until the 1980’s thanks to Jaron Lanier and VPL Research.

Figure 2 (above) on Sutherland’s Turing Award page is credited as being of one ‘Don Vickers’, could other such photographs be credited in a similar way? No. But Don Vickers’s ended up being much more interesting than I realised.

Sorcerer’s Apprentice

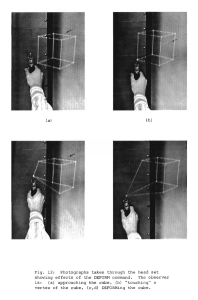

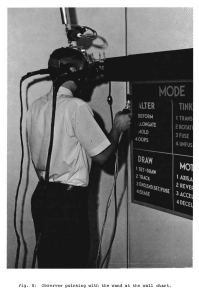

Sutherland’s studies of VR did not end with the Sword of Damocles, but were taken up by Donald L. Vickers, one of his students at The University of Utah. His 1974 thesis and the December 1972 edition of the lab’s Graphical Man/Machine Communications Technical Reports. They both contain pictures that I hadn’t previously seen of the Damocles system.

Vicker’s thesis describes the development of the ‘Sorcerer’s Apprentice‘, a magic-wand type interface for interacting with computer graphics while wearing Sutherland’s head-mounted display. As reported in his thesis, “a hand-held wand lets the observer interact with the objects by “touching” them, moving them, changing their shapes, or joining them together”. A claim, perhaps, to the first natural user interface in VR?

Unsurprisingly, Vickers reports in his thesis that “the ability to observe and modify three-dimensional objects in real time and in natural manner is very striking and very realistic”. In possibly the first acknowledgment of VR as a nauseous interface, I (MC) chuckled to read in the 1972 technical report that while “some can use it well the first time, but most require several sessions on the system to pass the “tolerance limit”– that point when the system becomes useful instead of merely tolerable.” How little VR has changed!

Howard Rheingold’s 1990 book Virtual Reality (which remains a fascinating look at early Virtual Reality) features an interview with Vickers – credited as Daniel, rather than Donald – with more history of VR’s early development that is often overlooked in the simplified histories that begin (and end) with Sutherland’s 1968 display.

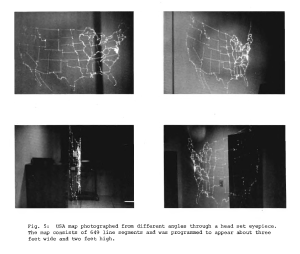

“The first fully functional HMD system was fired up in a laboratory in Salt Lake City on January 1, 1970. Daniel Vickers, who was a student at the University of Utah at that point, has been at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory ever since. He had the job of getting the systems running together and creating the software that would integrate them. I called him at Livermore and asked him if there was a specific day that he can remember when the first fully functional HMD system with eh first virtual world software was working. He laughed and recalled: “I remember getting the software up and running and making the first successful test on January 1, 1970, because the system consisted of several components that were always being used, and there weren’t too many time slots available to debug software. It was easy to get hold of the systems New Year’s morning because everybody else who used the equipment had been partying the night before. The first image was a wire-frame cube, two inches on a side. I called home and told my wife and brought my family over to see it. We felt it was a breakthrough. We could see real possibilities for the future.” (Rheingold, 1991, p. 106)

Rheingold’s history features a few more fascinating quotes from Vickers, who recalls “we discovered that the sense of presence was enhanced when we added the wand. The more senses you involve, the more complete the illusion appears to be” (Rheingold, 1991, p. 111).

Unfortunately, this discovery doesn’t solve the permissions problem. After leaving the University of Utah, Vickers seems to have worked at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory – primarily a nuclear weapon’s research facility co-founded by Edward Teller – until the mid 1990’s. Vickers credits the photos, like most of the photographs from Sutherland’s lab, to Michael Milochik, but I have not been able to track down any current contact details for either.

Fortunately all is not lost! We did hear back from the computer history museum who do have three lantern slides used by Ivan Sutherland in talks about the Sword of Damocles, of the head-mounted three dimensional display in their collection. The Computer History Museum is able to provide high resolution files – and critically, permissions – to use these images in publications, for a very reasonable $25 fee. Our quest to include at least some images of early VR was successful.

The Importance of Picturing Early VR

Images like these are critical for how we understand the history of Virtual Reality as a medium. Images make history, and their discoveries, feel more real and help students connect this history to their realities today.

Going back to these primary sources also allows us to go beyond the often overly simplistic historical narrative of Sutherland and the Sword of Damocles. Vickers’ memory of January 1 1970 reminds us of what an exceptional technical achievement these early head-mounted displays were, but also how fundamental most of the qualities of XR are: Sutherland and Vickers could be describing a Quest 3 headset when discussing interacting with their early VR prototypes, and the impact of interactivity on presence and immersion.

To end with a further compliment to the Computer History Museum: the physical device used in Sutherland’s Sword of Damocles – the head-mounted three dimensional display – is held in the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California catalog number X1044.90. No sign of Vicker’s magic wand, though.

Figures 7 & 8: low resolution photographs of Sutherland’s head mounted display, via the Computer History Museum.

If anyone finds themselves in Mountain View, everyone publishing VR books would sincerely appreciate it if you could pop by, take a few high-resolution photos, and share them with a creative commons license for everyone to use.

References

Sutherland, Ivan E. (1965) “The Ultimate Display,” Proceedings of the IFIP Congress, Vol. 2, pp 506-508.

Sutherland, Ivan E. (1968) “A Head-Mounted Three-Dimensional Display,” Proceedings of the Fall Joint Computer Conference, Vol. 33, pp 757-764.

Vickers, Donald L. (1974) Sorcerer’s Apprentice: Head-Mounted Display and Wand” University of Utah Computer Science Technical Report [link]

Vickers Donald L., (1970) “Head-Mounted Display Terminal,’ Proceedings of the IEEE 1970 International Computer Group Conference, Washington, D.C., pp. 270-277.

Evans, David C. & Stockham, T. (1972) Graphic Man/Machine Communications. RADC-TR-74-207 Technical Report, University of Utah.

Rheingold, Howard (1991) Virtual Reality. Mandarin: UK.

Roquet, P. (April, 2023) Learning from VR Motion Sickness. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). link