Platform art & the actually existing metaverse: An interview with Jeremy Bailey

In a recent paper published in Information, Communication and Society, I interviewed four artists working with augmented reality (AR) face filters. The article discusses the role of social media platforms like Meta and Snap in the definition of an “actually existing metaverse,” that is, an alternative vision to the hyper-immersive 3D worlds most associated with the term (think Meta Horizon, or even Second Life). This vision, conveniently grounded in Meta’s very vague definition of metaverse, factors in the reality of social media as a persisting paradigm for digital sociality and self-expression. My main argument is that, while Meta has officially pivoted away from the informational Pandora’s box that spawned the demons of “fake news” and hyper-politicized filter bubbles (and subsequent content moderation headaches), it has veered towards more tech-forward, immersive, and playful experiences. AR face filters, I argue, are one example of the company’s post-Cambridge Analytica “artistic turn,” which is marked by the investment into a more aestheticized, speculative form of digital identity—one designed to draw Meta’s users into a new interactive dimension while keeping them anchored to the Facebook social graph.

As mentioned, the article draws from interviews with four artists who have worked with the format creatively and reflexively: Jeremy Bailey, Leo Selvaggio, Jessica Herrington, and Lark Spartin. Not mere early adopters, these artists have written or created statements on AR art and its implications in terms of renegotiating the relationships between art, institutions, and the public. For the CAVRN website, I am publishing an extended selection of quotes from my interview with Jeremy Bailey, to enrich the perspective already given in the ICS paper.

Nicola Bozzi: What drove you to AR in the beginning? What was the thing that most fascinated you about this particular form of expression?

Jeremy Bailey: I was introduced to video art in college between 2003–2006, to a period in the 1970s where performance for the camera was the primary kind of method that artists were using for making work with video. And that really was about investigating the camera in terms of control: is it acting as a machine? Is it using me? Am I performing for it or is it performing for me? And there was a lot of dialogue around artists, artistic control, dissemination, society… Do we mimic television or do we break free of the norms that have been imposed upon us? There was a lot of feminist, queer video. And so my question at the time was simply: what’s changed about the camera since the 1970s and what are we performing for?

I became really interested in what was possible in real time, because in the 1970s there was a lot of conversation around the echo. Like, if you look at that video by Nancy Holt and Richard Serra, Boomerang (1974), they are exploring what it’s like to hear your voice as you’re performing on a loop, like on a slight delay, and the psychological or cognitive load that imposes on you in terms of self-reflection and identity. Because we’re often not conscious of our consciousness. So, in that video, there’s kind of that self-reflective levity that’s introduced, which we all know or maybe we don’t all know, but in video performance art resulted in a lot of personas. It was kind of: I’m performing for the camera, okay, so it’s not me.

“I quickly realized I can now kind of attach things to my body. And what does that mean? You know, that’s really changing how I perceive myself.”

So I always invented a persona, as I was investigating these tools. And I also simultaneously found some video scripting software, like programming tools for artists that could do real-time video processing. I started to play with filters, but they were just algorithms applied to the image. Then there was OpenCV, which is a computer vision plug-in originating from academia, and you could start to use all of these different types of tracking—face tracking, eye tracking… You had to do a lot of manual work to get things to work, but I quickly realized I can now kind of attach things to my body. And what does that mean? You know, that’s really changing how I perceive myself. I was just playing, but then I realized there was a lot of hype built into it and I started to kind of make fun or play with that.

Nicola: Beyond video, what technologies were the turning point that really ushered in the “new media artist” persona?

Jeremy: The big change for face filters came from an artist named Kyle McDonald. He’s still around. And he started taking academic work and making it available to artists. He made a software called Face OSC, a desktop program, and OSC (Open Sound Control), a communication protocol between computers and other devices that gave you all the coordinates of the face, the nose. I started making work with that pretty frequently.

The other big breakthrough was the Microsoft Kinect. I was really fascinated with it because, in 1969, the Sony Portapak came out and that’s where video art came from. It was the best selling camera ever up until that moment in time, so actually the best selling consumer electronics product in history. And then the Kinect became the best selling consumer electronics device in history, but not for its intended use, not for video games, but because artists were using the technology. Which I found very exciting as a concept. And then I started creating suits and stuff, and I had this idea of creating what I call the “Gundam Suit,” this painting and war suit that was all software. The Kinect made it possible for me to build this suit and then start performing with a digital layer over my body. And obviously, like I said, I made fun of it. Mostly my strategy was to kind of deconstruct my identity, my white male identity. But that’s all because of that history that I was trying to be a part of. That goes back to the 1950s, 60s, 70s, rather, where you’re like really aware, self-aware of your image and persona within the context of technology.

Nicola: Speaking of context, when did you develop your satirical persona to start making fun of Silicon Valley speak?

Jeremy: Starting in about 2010, I start working at a startup which grew to become a big company. But a lot of the rhetoric inside that company, I started to take that as material for my character. And, you know, sometimes it was so silly. I still work in software and, you know, a lot of what were early start-up ideals—there’s a lot of ideology built into agile software development, for example—had a manifesto just like the Fluxus manifesto, and a lot of these ideas became not just software company ideas, it was like mainstream culture. Now it’s really obvious, but at the time people thought I was crazy and not necessarily really understood, but the aesthetics of narcissism, everyone being a brand or having a persona, that was stuff that was being talked about in the 1970s as well. There’s an essay by Rosalind Kraus called The Aesthetics of Narcissism that I’ve always gone back to, because it’s a really good reference point for me in terms of asking: is any of this really that new? No, they always say the future is here. It’s just not evenly distributed.

Nicola: What motivated you to use tools offered by big platforms like Snap and Instagram?

Jeremy: With Snapchat there’s a little bit of a personal story. Back in 2008 or so, they approached me to come and work with them to build filters as a function of the application, because I had a video where I turned my partner into a unicorn, or something like that. And they’re like: “We imagine a world where everyone is a unicorn, you could come and work on that with us.” It didn’t work out, because they said they would own all my intellectual property, but they ended up being inspired by what me and other artists were doing.

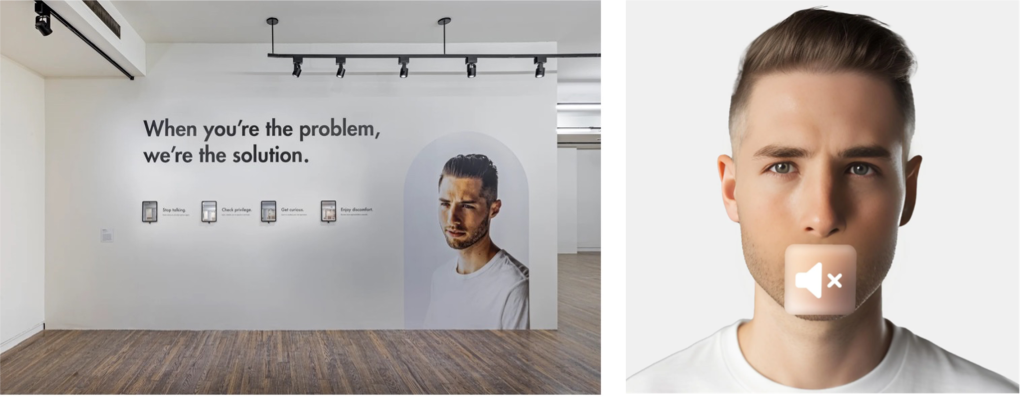

Now, I do use a lot of the Snap tools, because they’re quite good. But also, if you think about what we just said about the future being unevenly distributed, at a certain point it was like: “There’s Instagram, there’s Snap, there’s TikTok, they all have AR filters. Why should I be continuing to make AR filters?” But I realized this is culturally relevant now. It wasn’t before, and now it is. So I just started circulating my filters and building them in those environments because it I had always been asked: “How come I can’t get access to your filters?” And I didn’t feel that comfortable with it, but I started to work on a project where I’m not in the work—the filters are the work and they’re available to other people. That was a hard jump for me to make, because I’m usually making fun of myself in the work, and if my body is not present I am making fun of you, because you’re wearing the thing. This work, however, is framed within a context of a critique of white identity, or unpacking white identity, so it made sense there. I created a fake company called Whitesimple, and all of the filters are presented as tools for white people who are the problem to become the solution. But it makes sense for that work to exist and be accessible through Snap, so when the show closed it is now on the web. I haven’t monetized it, there was a lot of press for the work and I was just happy people got to experience it.

I have another project focused on AR beauty called PAC, in collaboration with Heran Genene Heran Genene and a diverse range of artists (SHAWNÉ MICHAELAIN HOLLOWAY, allapopp, [{“CIBELLE”(CAVALLI}BASTOS)], Dillea Himbara, B, garçonnnne). We did both Instagram and Snapchat filters for that and then released all the source code. I was working with trans artists to unpack filter dysmorphia. Part of that project was working with artists and asking them what tools they wanted to use, and they really wanted to use Instagram, which surprised me.

“And if you look at the most popular filters, they really encourage beauty as the primary outcome, normative beauty, which is the reason it’s depressing for me. If I go back to that 1970s moment and I mentioned feminist and queer voices, you know, that was about disrupting normativity.”

The reason I did that was I was very depressed about what I was seeing in terms of not just the use of filters, but the filters being created. And if you look at the most popular filters, they really encourage beauty as the primary outcome, normative beauty, which is the reason it’s depressing for me. If I go back to that 1970s moment and I mentioned feminist and queer voices, you know, that was about disrupting normativity.

It was interesting to see that queer identity might be one that erases identity or masks identity. There’s obviously a lot of pressure to manage that online persona that we now associate with Andy Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame. I know it’s quite cliché at this point, but the people are feeling a tremendous pressure to hide, and so deletion or erasure has become sort of the primary mode of identity expression, which I don’t think we would have predicted in the Internet era of 1999 when, you know, that was hyped up in media like “Get on the Internet, anyone has a voice.” Now it’s like: “I want my voice to be as small or as controlled as possible, because I don’t want to be hated or canceled or erased.” And so I’m going to take the preemptive act of tracing myself, my identity, that sort of stuff.

Nicola: What do you think about digital art that is platformed by nature? Are you worried about the loss of criticality in this respect?

Jeremy: In the 1970s, everyone getting access to a video camera led to a cable access movement that led to more communities and more voices in cinema and television. So I don’t think it’s a negative. I would always be on the side of enabling access to more people. Obviously when you get more people, you get less nerds. But you get new experiments and new expression that you didn’t expect, which then, you know, repeats the cycle. So the criticality I’m less worried about because I think there’ll always be academics or people that are taking that material from popular culture and reinterpreting it and talking about it critically. And I would assume if I was in school right now, I would be really interested in the topic of filter dysmorphia. So the criticality or the number of people talking about technology critically is way higher. When I started, like I said, no one even understood what I was doing.

Nicola: I was wondering: how do you see the role of artists in this, and what opportunities come with it?

Jeremy: In my artistic practice, I founded an accelerator for artists, which started out satirically. But then I discovered that artists could make a greater contribution to the world, and earn money. And I was like: “Okay, well, sometimes it’s not enough just to highlight the problem. Sometimes I’m interested in being part of the solution as well.” But the truth is, the average artist makes less than $10,000 a year, you know? And so the artist is the most highly educated demographic within the poverty class. Historically, if you look at who’s benefited from that, it’s been the upper echelons of society, the bourgeoisie or the church. But nowadays it’s the platform companies. And you know, there’s a large movement in my day job against those platform companies like Google, YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook as having exploited the artist for their own financial gain. The artist has become the content engine for their advertising network. And so a lot of my energy goes towards helping artists build their own platforms.

For example, there’s no open-source filter platforms, which is kind of interesting from an NFT perspective. So, with Robert Sakrowski, who directs panke.gallery in Berlin, we founded a little website called openAR. Our idea was to create an open platform for selling geo-located, sculptural AR, but not body-based, because that still wasn’t possible. You remember Fluxus had happenings, right? And the concept of a happening was “Let’s get everyone together to break the social machine and social fabric.” But I haven’t heard much many news items about collective action in online space.

There’s a great book on this topic that inspired me years ago: Uberworked and Underpaid by Trebor Scholz. He kind of espouses that idea that the workers should own the platform. And obviously this is the Web3 movement that we hear about. It hasn’t really materialized to the extent that artists are still struggling, they’re cobbling together multiple lines of revenue. But it is much different than when I started. Now, what will artists do with that? Will they use it to drive more creative exploration and it will be a Fluxus movement, or will it be a yuppie movement? I think, given that the artist is starving, we’re likely going to see artists experiment with commodity a lot more. And I don’t know what that’s going to look like, but it’ll be interesting.

If you think about the stages of representation, obviously capital is the biggest mirror we have, and with the most control. We perform for capital more than anything else and, from my perspective, the owners of capital, in terms of power, are the platforms. Artists really need to be aware of how those platforms manage them or how they perform for them. Our digital reflection is in the algorithm and that’s what we perform for most.

References

ANU School of Cybernetics. (2025, March 25). Can Art create the metaverse? https://cybernetics.anu.edu.au/news/2025/03/25/Can-Art-Create-The-Metaverse/

Apologize to America. (n.d.) Apologize to America. Retrieved April 14, 2025 from https://sites.google.com/view/apologize-to-america/home?authuser=0

Bailey, J. (2022). Whitesimple. https://www.jeremybailey.net/collections/startups/products/whitesimple

Bozzi, N. (2024). Meta’s artistic turn: AR face filters, platform art, and the actually existing metaverse. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2024.2427116

Krauss, R. (1976). Video: The aesthetics of narcissism. October, 1, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778507

Meta. (n.d.). What is the metaverse? Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://about.meta.com/uk/what-is-the-metaverse/

openAR. (n.d.). About openAR. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://openar.art/p/about

panke.gallery. (n.d.). panke.gallery. Retrieved April 14, 2025, from https://www.panke.gallery

Scholz, T. (2016). Uberworked and underpaid: How workers are disrupting the digital economy. Polity.

Recommended citation

Bozzi, N. (April, 2025). Platform art & the actually existing metaverse: An interview with Jeremy Bailey. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). https://cavrn.org/platform-art-the-actually-existing-metaverse-an-interview-with-jeremy-bailey/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.