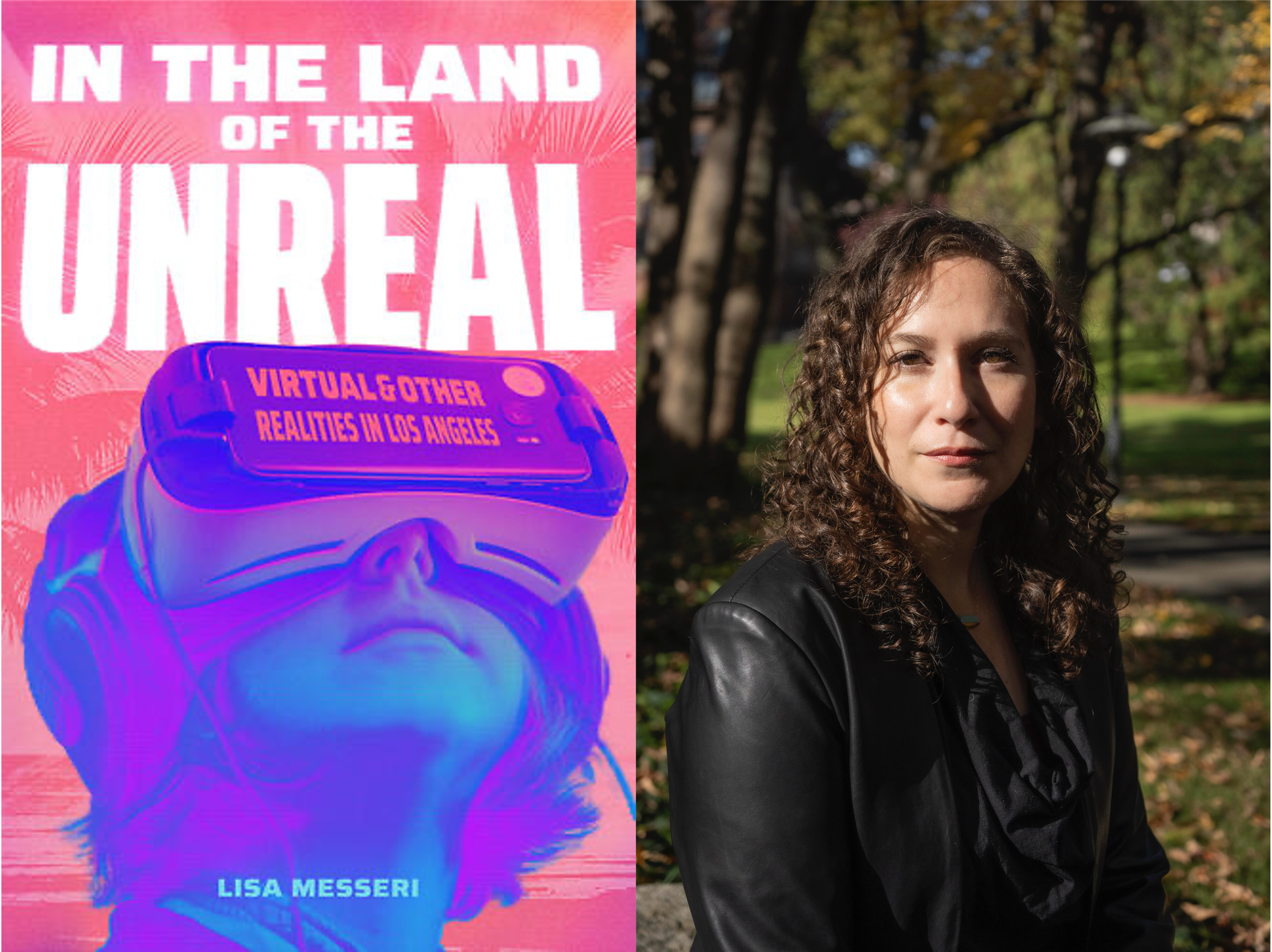

Book Review: Lisa Messeri’s “In the Land of the Unreal: Virtual and Other Realities in Los Angeles”

This review was originally published in the International Journal of Communication, Volume 18 (2024), and is republished on CAVRN with the permission of the author, Maxwell Foxman. You can find the original review here.

Despite virtual reality’s (VR) widespread availability (and lower price) since 2016, much literature surrounding it remains relatively speculative; there is no shortage of journal articles exploring its potential uses and effects (e.g., Girginova, Cassidy, Foxman, O’Donnell, & Rawson, 2023). It is difficult to find accounts of how head-mounted displays (HMDs) are used. For those interested in the technology’s broader and current cultural saliency, Lisa Messeri’s In the Land of the Unreal: Virtual and Other Realities in Los Angeles is a much-needed addition to apprehending this increasingly ubiquitous medium.

VR’s impact as it embeds itself as an entertainment format lies at the core of Messeri’s manuscript. She first roots VR as a technology of the “unreal” or “the experience of living in and navigating between multiple realities” (p. 16) with the “erosion of the illusion of a singular reality” (p. 66). Then, to demonstrate how times and places spark producers’ and consumers’ imagination and implementation, she situates it within Los Angeles (LA). An anthropologist, Messeri performed a yearlong ethnography in 2018 (p. xv), just after the apex of VR’s hype cycle. During this period, she attended enthusiast meetings and observed various studios. She steeps her work within this geography, pulling from experiences and conversations with those from the entertainment industry to illuminate the local reality and possibilities that they are trying to realize and communicate.

Messeri divides the book into three sections: fantasies of place, being, and representation. Each begins with conceptual examples followed by grounded fieldwork. After an introduction, the first part examines how LA’s “technological terroir” (p. 29) shapes the ethos for VR usage. In the chapter “Desert of the Unreal: Histories, Futures, and Industries of Reality Repair,” she plumbs the city’s history, where locations like Disneyland were designed to be “reality made fantastic” (p. 40). LA is a city of “worldbuilding,” where fiction can be a “testing ground for reality” (p. 47), and “Hollywood expertise slips beyond the confines of the screen, just as it did when the entertainment industry was mobilized for the war effort or Disney imagined the urban fantasy of EPCOT” (p. 47). Such utopian visions also displace other worldviews, like those of the indigenous population (p. 34).

The book’s theoretical foundations are probed next in “Realities Otherwise: Understanding VR by Experiencing LA,” where Messeri applies LA’s many facades and the hyperreal to develop her notion of the “unreal,” which she scrutinizes through a months-long stay at Technicolor Experience Center (TEC). There, friction arose from conflating VR with cinema, leading to roadblocks regarding the center’s viability because of its technological focus.

Messeri then turns to common subjects for VR research. In “Being and the Other: Dismantling the Façade of the Empathy Machine,” through vignettes of influential immersive journalist Nonny de la Peña, who translated “laboratory research into language more readily accessible by her nonacademic peers” (p. 114), Messeri concentrates on the association of VR with concepts like immersion and the “empathy machine.” She highlights how the term could “assist in overcoming societal strife and inequalities” (p. 101), but only to a privileged few, making it an analogy to apprehend how fantasies of VR’s promise spread. Realizing the concept’s grandiose yet haphazard deployment by enthusiasts, the following chapter rethinks a more affective and communitarian form of immersive empathy through observations of Embodied Labs, a startup expressly focused on training caregivers.

The book’s final section considers representation. The sixth chapter describes “VR’s Feminine Mystique: A Technology of the #MeToo Moment,” where women are recruited into the industry while still stereotyped and mistreated, as exemplified in a detailed account of Upload—a company and facility in which Messeri took courses and conducted interviews. Her findings reveal the contradictory expectations of VR “naturally” fitting with women while cultural roadblocks persisted for them. After a final chapter examining specific skills VR affords that support more diverse job opportunities in tech, her epilogue discusses how a “paradox of unreality” (p. 204) has consequences beyond devices, leading to cultural moments like storming the U.S. Capitol. Ultimately, a fractured and multiple unreality has become an existential norm.

Messeri’s work arrives along with a slowly growing tide of critical research (see: https://cavrn.org) on culture (e.g., Evans, 2018; Nakamura, 2020) and fantasies about the technology (Carter & Egliston, 2024). These investigations situate VR as not on the verge of adoption but as already present in social media, digital platforms, and games (e.g., Harley, 2020). While these works take VR out of the realm of speculation and science fiction, they still tend to home in on its importance to specific industries.

In the Land of the Unreal provides a timely alternative narrative by emphasizing LA, a place that uniquely frames VR as an entertainment format and emerging technology. Messeri grounds this assertion with explicit cases. Whether articulating historical vignettes on the masculinist histories of Upload or terms like the “empathy machine,” she uses real-world and thick descriptions to elucidate how VR is perceived in the city. Her approach also extends to people: Technicolor Experience Center director Marcie Jastrow highlights the tensions of VR in Hollywood; Upload’s vice president of education Jacki Ford Morie is a significant spokesperson for understanding the opportunities VR offers women while managing toxicity; and Embodied Labs founder Carrie Shaw both skillfully pitches the concept of empathy to a broader public and provides a novel interpretation of the concept, which “matters . . . as a catalyst by which the individual might find additional ways of relating to and caring for one’s community” (p. 152).

These stories and ideas can inform other work, especially as there are calls for reimagining the techno-utopian concepts surrounding VR and the metaverse (Girginova, 2024). Messeri’s descriptions of how the Women in VR group acted as a voice of empowerment during the height of the #MeToo movement and resulted in a feedback loop of support and amplification for women working with the technology echo my own experiences with the New York chapter (Foxman, 2018). Similarly, her accounts of affective empathy and the history of de la Peña add much-needed reasoning as to why the theory resonates with the public, even while being rejected as dubious. As Messeri (2024) puts it, de la Peña “transformed VR from a laboratory tool for studying presence to a storytelling tool for eliciting emotion through an embodied experience of being at the scene of an event” (p. 123), which is appealing to media producers.

“Messeri’s study notably reminds that rather than assuming VR’s dissemination will be uniform, there is a constant need to consider the fantasies and representations of marginalized communities that deviate and remain under the radar of often hegemonic utopian perspectives.”

Her most substantial contribution moves beyond these excellent portrayals and examples to reimagine our relationships with VR—a political mission to go past the male-dominated tech and game industry that hovers at the periphery of her work. She brings a different view to center stage, especially in the final chapters. Here, the activities of LA producers underscore a “xenofeministic” (p. 177) relationship with the technology, repurposing and actively embodying potential applications of VR beyond the dominant and often essentialized imaginary. She describes her and her subjects’ efforts as a “recursive project” (p. 197): it flows from women (including herself) to tell the story of representation and bring a more meaningful version of that world into being. This project extends to other marginalized voices as well. Whether considering indigenous peoples in deciphering LA’s unreality or sharply critiquing the skindeep perception of VR, empathy, and race, there is a palpable desire throughout the book to expand the technology’s capability. Her work seems more necessary as VR normalizes. Much of what we think of as “virtual reality” may not persist in HMDs but instead be integrated into other media, game formats, and cinematic techniques as tech leaders push toward a more commonplace “spatial computing” (Mohamed, 2023). Messeri’s study notably reminds that rather than assuming VR’s dissemination will be uniform, there is a constant need to consider the fantasies and representations of marginalized communities that deviate and remain under the radar of often hegemonic utopian perspectives.

By the end of the book, a detailed and nuanced picture of VR emerges that exposes how “real” the technology is and has been for many decades. At the same time, Messeri showcases how VR (and LA’s) “unreality” will sway users and practitioners in the years ahead.

References

Carter, M., & Egliston, B. (2024). Fantasies of virtual reality: Untangling fiction, fact, and threat. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Evans, L. (2018). The re-emergence of virtual reality. New York, NY: Routledge.

Foxman, M. (2018). Playing with virtual reality: Early adopters of commercial immersive technology. Retrieved from https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8M05NH3

Girginova, K. (2024). Global visions for a metaverse. International Journal of Cultural Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/136787792312247

Girginova, K., Cassidy, K., Foxman, M., O’Donnell, M., & Rawson, K. (2023, April). The social grammars of virtuality: A review of social science XR research in 2022 (No. 1). Annenberg Virtual Reality ColLABorative, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://penn.manifoldapp.org/projects/social-grammars-of-virtuality-no-1

Harley, D. (2020). Palmer Luckey and the rise of contemporary virtual reality. Convergence, 26(5–6), 1144–1158. doi:10.1177/1354856519860237

Mohamed, K. S. (2023). Deep learning for spatial computing: Augmented reality and metaverse “the digital universe.” In K. S. Mohamed, Deep learning-powered technologies (pp. 131–150). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Nakamura, L. (2020). Feeling good about feeling bad: Virtuous virtual reality and the automation of racial empathy. Journal of Visual Culture, 19(1), 47–64. doi:10.1177/1470412920906259

Recommended citation

Foxman, M. (August, 2024). Lisa Messeri, In the Land of the Unreal: Virtual and Other Realities in Los Angeles. Critical Augmented and Virtual Reality Researchers Network (CAVRN). https://cavrn.org/book-review-lisa-messeris-in-the-land-of-the-unreal-virtual-and-other-realities-in-los-angeles/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.